KŌRERO PONO - THE STORY

The story of this church includes happenings that have occurred in few other churches. In its first ten years it was used as a place of worship, a courthouse, a fortress, a barracks, a prison and a ballroom, before being restored to a House of God, sadly not in its original concept of a 'missionary' church but in the new role of a 'settler' church.

This part of New Zealand history tells of the outreaching of the Good News of Jesus Christ into the lives of the people in this eastern part of New Zealand. Early in the 19th century, Mission stations were opened at Tauranga and Rotorua bringing the Christian message to the Māori tribes of those regions. Piripi Taumatakura, a liberated slave of the Nga Puhi who had accepted the Christian faith, was landed at Rangitukia in 1834 to carry the Christian message to Ngati Porou. By 1840 there were 1500 professing Christians in the East Coast area. No one is quite sure whether the Gospel first came to Opotiki from there or from Tauranga, but Reverend William Williams is quoted as saying on 12th November 1839.

"At Opotiki, Torere, Maraenui and Motu we have native teachers and schools but no returns. The congregations at these places collectively amount to not less than 800"

A request from local Māori saw Mr John Alexander Wilson, a C.M.S. Lay Catechist, landed at Ohiwa on 28th December 1839 accompanied by Chief Ngahuku and other Māori. For his mission site, Wilson chose a place in the present Fromow Road called "Hikutaia" where Bishop George Augustus Selwyn baptised the first local candidates late in 1842. A chapel, probably built of raupō, was erected near the site of the present church about 1843. In 1852 Wilson was transferred to Auckland by Bishop Selwyn and replaced by the Reverend C. P. Davies and later still by the Reverend T. Chapman. Sometime during 1857 the Reverend Rota Waitoa, the first Māori ordained Deacon, who served at Te Araroa, preached at Holy Communion in Opotiki.

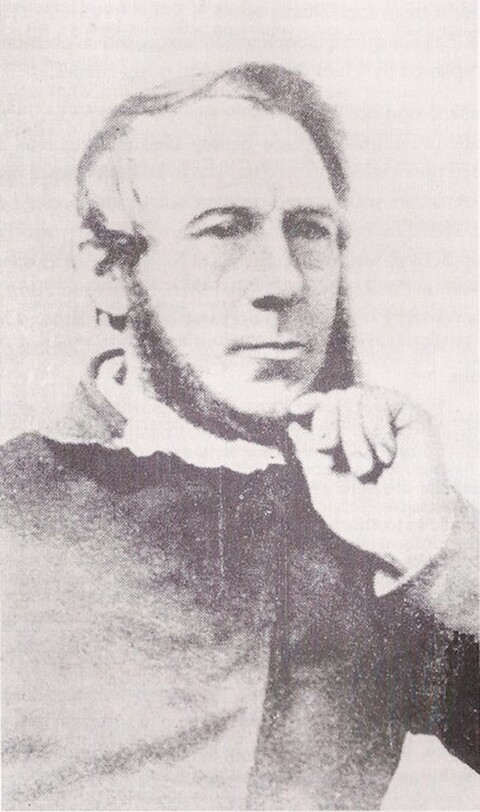

In 1859 William Williams was consecrated Bishop of Waiapu, and in the course of visiting this area decided to place Reverend Carl Sylvius Vōlkner at Opotiki as full time Missioner.

Vōlkner had originally come to New Zealand to work in a Lutheran mission in Nelson, but later offered himself to the Church Missionary Society (C. M. S.). He served at their school in Tauranga and then at Waerenga-a-Hika near Gisborne, where he was ordained Deacon.

So in 1861 Vōlkner and his wife arrived in Opotiki and moved to the new mission site, which he named "Peria". This was because he was struck by the resemblance of his call to that of St. Paul in the town of Beria (Acts 17:10). This remained the Vicarage property until 1996 and is next door to Peria House, a retirement home, where the original brass plaque may still be seen.

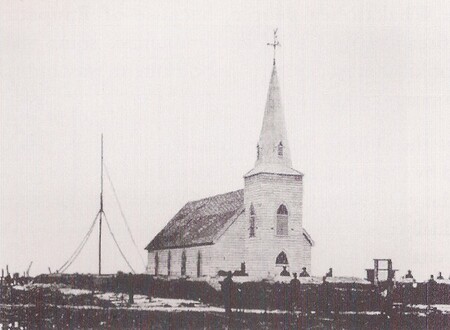

In September 1862 Bishop Williams ordained Vōlkner a priest at which time Vōlkner expressed a desire to have a wooden church in Opotiki. Local Māori promised to cut and supply timber and on 27th August 1862 a contract with Messrs. Bridson and Wilson, an Auckland firm, was signed to build a church sixty feet by twenty-seven feet. A copy of this contract can be seen in the porch of the church. While work started in 1862, the building was not completed until 1864, because all the timber had to be pit sawn and then hand wrought. This timber was obtained from the Otara and Waioweka valleys. The contract price was $500, with Governor Grey contributing a 'Koha' of $200 to assist the completion.

The design of the church, with its tall steeple on the west end, is more characteristic of Continental than of English churches, perhaps indicating the Vōlkner modeled it on churches he had known as a young man in Germany. This design was copied by a number of Māori churches east of Opotiki.

The Dedication service to open the church was on 30th January 1864, and the name given was "Hiona", being the Maori translation of "Zion".

During this time war had broken out in the Waikato and Taranaki areas, with a new and exciting faith springing up in Taranaki called the Paimārire, or the Good and Peaceful religion. This was founded by Te Ua and was a mixture of Old Testament morality, Christian doctrine and early Māori religion. A group of these people, who came to be known as "Hau Hau", travelled to Opotiki in late 1864, under the leadership of Kereopa Te Rau and Patara Raukatauri, to raise support for further fighting against the British.

While Vōlkner worked long and hard for the Whakatōhea people of Opotiki he made decisions that were to bring about his death, giving the Government an excuse to confiscate Māori land in retribution for his murder.

Briefly these decisions were:

- He chose to pass information to Governor Grey about Māori movements and fortifications hoping by doing so to prevent war. When this fact was discovered by Māori they believed he had abandoned them and was spying for the Government.

- In one of his letters to the Governor, Vōlkner complained that Father Garavel, the resident Roman Catholic priest, was bringing information from the Waikato tribes to Whakatōhea and stirring up the locals. As a result of this Father Garavel was removed by the Catholic Bishop Pompalier, and rumour suggested Garavel had been hanged in Auckland. The blame was laid at Vōlkner's door.

Some of Kereopa's relations had been killed by British troops at the Rangiaowhia mission station in the Waikato conflict. This resulted in Kereopa swearing "Utu' or revenge, on the church and missionaries.In February 1865 Vōlkner and Grace arrived back in Opotiki and were immediately taken prisoner by the Hau Hau, and held overnight. The next afternoon Vōlkner was taken before Kereopa who condemned him to death. After saying prayers, in which he forgave those who were about to kill him, he was hanged on a willow tree not far from the church.

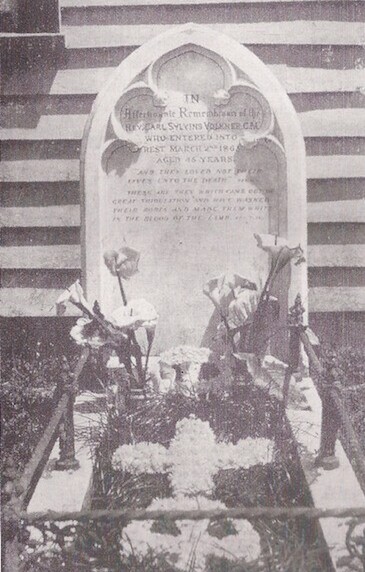

There have been many accounts of the treatment of Vōlkner's body after his death, but it needs to be remembered that there were no European witnesses. While it is certain that he was decapitated and the church desecrated by the spilling of his blood, no one can be sure what happened on that tragic day. Grace was also placed on trial on 5th March but it seemed that Vōlkner's death was enough, and Grace was simply kept in confinement. On 13th March Grace was able to bury Vōlkner's decapitated remains alongside the east wall of the church he had built.

Reprisals were undertaken against both the Whakatōhea people and the Hau Hau, who were driven inland by the East Coast Expeditionary militia. The desecrated church was turned into a redoubt and a prison, and martial law proclaimed by Governor Grey on 4th September 1865.

Five Māori were arrested for Vōlkner's murder, Mokomoko, Heremita Kuhupaea, Hakaraia Te Rahui, Paora Taia and Penetito. The trial took one day, 28th March 1866 and the jury convicted all save Paora.

The evidence against Mokomoko was week, the main point being that the rope from his horse had been the one used to hang Vōlkner. He along with the others were hung in Mt. Eden jail on 17th May 1866.In 1875, with a European population of around 400, Bishop Williams appointed Reverend A.C. Soutar as Opotiki's first vicar and on 21st November 1875 the church was rededicated and named The Church of St. Stephen the Martyr in honour of Vōlkner. In hindsight this reason was incorrect because the definition of martyr is someone who dies for his or her faith. While no one can question Vōlkner's faith, and his love and good intentions for his parishioners, his death was more for political reasons than religious ones. The Whakatōhea people, because of raupatu or land confiscation, now lived in communities some miles out of Opotiki and so Soutar's appointment was limited to European the community.

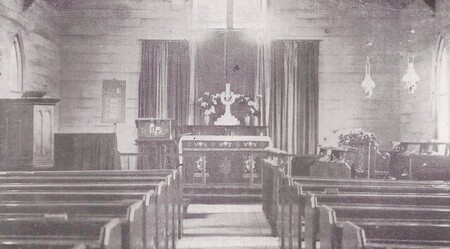

Thus the church, built specifically for Māori, was no longer used by them and its control passed out of their hands. In years following the 2nd World War, local Māori have gradually returned to the Parish family and today play a strong and vital part in the Church's life.In 1910 the church was extended to the east with the addition of the Sactuary area. This extension placed the Reverend Vōlkners grave immediately under the church. The original headstone was moved and set into the east wall where it can be seen today. The iron raisling around the grave are still visible by looking thorugh the baseboards ofthe chruch. Inside the church a marble maker has been set into the Sanctuary floor immediately above the grave.The centenary of the Church in 1964 was marked by the gift of the sandblsted windows from the neighbouring Māori Pastorate of Te Kaha. A description of these windows can be found at the back of the church.To cement the relationship between Māori and Pākehā in the church, work began in 1978 under the guidance and leadership of Mrs. Grace Maxwell to install 'tukutuku' panels around the Sanctuary walls. This took Māori parishioners eighteen motnhs to complete and in April 1979 bishop Paul reeves dedicated the panels. At the same time the 'taniko' kneelers were made for the Sanctuary rails.